(Dedicated to and in memory of Professor Mahmoud Hamid

What is Eco-Tourism?

According to The International Ecotourism Society (TIES), “ecotourism is about uniting conservation, communities, and sustainable travel” (TIES, 2010). TIES principles of ecotourism are for eco-tourists to:

- Minimize impact;

- Provide positive experiences for both visitors and hosts;

- Build environmental and cultural awareness and respect;

- Raise sensitivity to host countries' political, environmental, and social climate;

- Provide direct financial benefits for conservation; and

- Provide financial benefits and empowerment for local people.

Traveling anywhere, I always try to follow the first two. This was the first time I also did the others, especially the third and fourth.

In addition, after being with the Bishnois, I feel another principle of eco-tourism is to immerse in the ecological way of life of the community you are in, and to become one with the people and environment you are in. This means, live amongst them, as they live themselves. Learn their language, or at least how to greet them. Learn from the people, their practices, their wisdom, and make a commitment to make their eco-friendly lifestyles a part of your life. Take their lives into your life; take their ways home. Find a way you can assist the community with their environmental challenges. This will ensure that the impact on the environment and the culture is minimal, and that you are enjoying yourself as well as giving back to the Earth.

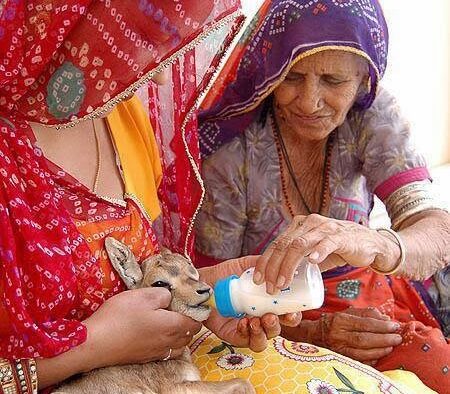

“Sowmya Bishnoi.” Sitting in a small Bishnoi temple outside Jodhpur, Rajasthan, amidst green rolling hills, and some chinkara (a form of antelope) babies, Priest Visudhanand made me an honorary Bishnoi.

“Bishnoi is not by birth,” he explained through my translator and friend, Mr Khemkaran Bishnoi, “it matters about the work you do”.

I was touched to a point of tears of joy. I had been waiting for two years to meet the Bishnois, and within a matter of a few days, they graced me with such a high honor of being one of them. They were happy to meet someone from afar who had studied Environmental Security and Bishnoism, and loved their religion and practices.

But what does it mean to be Bishnoi?

Basics of Bishnoism

Bishnoi literally means “29” (Bis = 20; noi = 9), and the Bishnoi guru, Jambeswar, gave 29 rules for followers to observe. Thus a person is Bishnoi if he/ she follows these rules. Rules are about general health and well-being, women’s health, and the environment. Known as India’s first ecologists, Bishnois love their animals and plants to a point where they place environmental security above human security.

The work of a Bishnoi child starts early—at the age of 1 month, when the child can be separated from the mother for extended periods of time. A simple baptism gives the child the right to be a Bishnoi, and the mother is responsible for cultivating the child’s life. Other than that, “Bishnoi women and men have the same duty. It is only that the women are emotional, so they practice the religion whole-heartedly and fully. They really care,” my interpreter translates.

Being an eco-tourist

Part of being an eco-tourist is becoming one with the people. I went with another UPEACE ESP student to meet the Bishnois. We spent the weekend with the Bishnois at their village camp resort, and got a quick glimpse at their lives. Because the Bishnois truly believe in caring for the environment, there’s a deep-seated knowledge that everything is eco-friendly, without question. Guests stay in a village-like atmosphere with cow-dung and hay huts, and buckets for bathing.

“Cow-dung?” you might be thinking. Actually villagers across India use cow-dung for many purposes, including fuel and building huts. It is a natural antiseptic, and, combined with a few herbs, produces a most calming scent. Entering the hut, I felt refreshed, and a wave of peace came over me.

One hut serves as a kitchen, and the chef, a member of the family, cooks using coals to light the fire. It’s the same as a regular home in the village. All the products used in meals are locally grown, from millet to make chapattis to milk for ghee to sangri, the local fruit from the Khejari tree, the most beloved of Bishnoi trees. The fruit is not picked; rather, it is collected after it naturally drops to the ground.

The sanded area is spacious and beautiful, and can double as a bed if you want a blanket of stars. In the desert, with the lights of the city far away, you can see more stars than you even knew existed. It’s totally safe, you might get a frog to keep you company, or grasshoppers to sing you to sleep.

I learned a little bit about being Bishnoi and walking with nature when we went on a drive through the Bishnoi land, an empty space used for grazing. I learned about silence, when we saw some deer. They were not scared of us, just happily grazing as we watched. I learned about how to approach black buck, a rare form of antelope whose population decreased during the 20th century. Our young guide, also a family member, explained that we should “walk from behind, and then come across.” He reminded me to go slow and be soft. We got as close as possible to just observe the pack playing; we didn’t want to go too close, because it might disturb the animals.

I also learned about freshly popped millet—watched every moment of our host making it from harvest to seed and then enjoyed the savory taste in my mouth. Bishnois do not waste, and their foods are made fresh every day.

Khemkaran Bishnoi makes popped millet on the home stove

Finally, if eco-tourism means becoming a part of the people you are with, then one evening stands out for me. Our host took us home, where the women and girls dressed me in their finest jewelry. Adorned like a bride, I felt I was Bishnoi, if only in heart.

I was pleasantly surprised at the simple nature of the younger generations I met. Bishnois are known for their decent standards of living, without having much poverty, crime, or violence (except the people who have died to save a plant or animal).

Spreading the seeds of sweetness

Not a lot of people know about Bishnoism. Even in India, the only people I encountered who had heard of this community lived in Rajasthan, and mostly in the Jodhpur district. Less than one million are counted in Bishnoism. When asked how we could spread the knowledge, the priest told me in no uncertain terms: “We cannot spend much time on publicity; the work would not be done. The time is spent in grassroots. Word of mouth is the best way. One to one. Teach our principles.”

Is it better to raise awareness on caring for nature like this? Maybe it would work—after all, door-to-door campaigns have been used for every known purpose. I’m just not sure if this would fit in the framework of Bishnoism, who are unassuming peoples, and prefer not to push their religion onto others.

On the other hand, something the Bishnoi priest told me that everyone should do is to have a havan in their homes. A havan is a fire burnt using herbs, coconuts, and ghee. “If every home in the world made a Havan every day, the air would be clean and pure”. Unfortunately, while this would fall into the guidelines of the religion, I mentioned to the priest that at least in the US, this would be a fire hazard! Is there a way to perform havan and purify the air that would fit into the legal restrictions around the world? I wonder if together, we could devise a way to cleanse our atmosphere of the pollutants we put into it every day.

It seems to me that it would be hard to be Bishnoi elsewhere in the world, because of the clash of cultures. So I asked the priest for just one simple message to the world: “One thing we should do — be compassionate towards lesser beings and don’t touch green trees.” This, I believe, is my duty as an eco-tourist and now as an honorary Bishnoi: to take the lessons I’ve learned back with me and incorporate them into my daily life; to increase environmental security through awareness; and to, thus, be Bishnoi by the work I do for nature.

History of Bishnoism

Bishnoism (literally, 29) is a religion founded by Guru Jambeshwar (Jambaji) in the 1400s. The religion has 29 tenets its members must follow. Of these, the largest group, eight, specifically delineate man’s responsibility to nature: to protect it, to secure it, to sacrifice for it. Caring for plants and animals is not because nature has something to give, as traditional thought on environmental security purports. In this religion, the main element of environmental security is the environment. Religious security through martyrdom is granted and a place in the after-life is achieved through dying in an act of protecting nature (Soule, 2003).

A relatively unknown group, Bishnoism has about 600,000 million followers worldwide, most of whom live in Rajasthan, India. Others have migrated into nearby states in India, including neighboring Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Haryana. Pankaj Jain (Jain, 2010 ) writes that although Bishnoism may have ties to Hinduism, Bishnois have even “escaped the attention of scholars of Hinduism”.

The 1700s

The most famous act of martyrdom is when, in the 1700s, the maharaja’s army was charged with collecting timber to build up the fort. Known as the Khejrali Massacre, it started with a young woman, Amrita Devi, who activated 363 Bishnois to hug trees. They were consequently killed by the army. When the king heard of the atrocities, he issued a royal farman, or edict, to protect the religious environmentalists, providing religious and environmental security all at once.

Greatly distressed by the violent acts committed, and moved by the courage of the Bishnoi community, the king apologized for the mistake committed by his officials and issued a decree, which was engraved on a copper plate, and still hangs in the Jodhpur palace as a reminder. The farman prohibited the cutting of green trees and hunting of animals within the boundaries of Bishnoi villages. It was also ordered the state would prosecute any individual who violated this order, even unknowingly. Today, a temple is being constructed in Khejarli in memory of the event.

Contemporary Bishnoism

The movement started by Amrita Devi continues to inspire Bishnois to fight for and protect animals and plants in their territory. The protocol begun in the 1700s has been adhered to until today. Through the constitutional law, animals and plants are now protected in Bishnoi villages. Bishnois continue to save animal lives from pleasure hunters and others in the region. The government highly recognizes the Bishnoi work to save their local environment; there is even a governmental award, the Amrita Devi Award, honoring those who sacrificed their lives for other living beings (Mehrotra, 2009).

I don’t know everything about Bishnois. After all, I only spent a few short days traveling with them. I had ample opportunities to interview men and women of the community, leaders from various walks of life. Poverty is non-existent, and domestic violence is a rarity, according to the villagers I spoke with. The one major issue we observed and spoke about with our guide was an open-pit mine, just outside the Bishnoi land. Sadly, though the Bishnoi villagers have protested, the governmental response has been negative. The law only protects the Bishnoi land. Unfortunately, while the mine is technically not on Bishnoi acreage, the consequences are grave: noise, air, and water pollution are all expected outcomes; animals may be scared away, soil is depleted of natural minerals, and the community in general is disturbed.

Works Cited

Bishnoi, K. (2010). Bishnoi Village Camp & Resort. Retrieved March 10, 2011, from Bishnoi Village: http://bishnoivillage.com/bishnoism.html

Jain, P. (2010 ). Bishnoi: An Eco-Theological "New Religious Movement" in the Indian Desert. Journal of Vaishnava Studies , August: 19.1.

Mehrotra, R. (2009, February 6). And now “Conservation Reserves” in Rajasthan in 12th Birding Fair :. Retrieved March 10, 2011, from Dedicated to 'Communities in Conservation': http://www.birdfair.org/12thBirdingFair.pdf

Soule, J.-P. (2003, February). The Desert Dwellers of Rajasthan: Bishnoi and Bhil People. Retrieved March 10, 2011, from The Native Planet Website: http://www.nativeplanet.org/indigenous/cultures/india/bishnoi/bishnoi.shtml

TIES. (2010). What is Eco-tourism? Retrieved October 11, 2011, from The International Eco-tourism Society: www.ecotourism.org