Several factors underpin the relationship between India and Japan. The two nations expound common strategic interests in the region and promote shared values of democracy, pluralism and prosperity. A civilizational thread hallmarked by Buddhism and Vedic concepts also binds the two Asian powers. Furthermore, India and Japan have many similar experiences in the field of art, music and traditions that have shaped their contemporary intercultural dialogue.

An exemplar success of this cultural exchange is the Mithila Museum in Japan. A brainchild of Mr. Tokio Hasegawa, the museum hosts the largest collection of Madhubani art in the world, with over 3000 works, along with Warli and Gond paintings, as well as pottery from Imphal and other Terracotta sculptures. It is perhaps fascinating if one thinks of what could be the possible reason for a Japanese musician and culture enthusiast to come all the way to India in search of Madhubani art and artists, and provide them patronage in Japan. This curiosity led us into a conversation with Mr. Hasegawa and unraveled ideas and realizations that would otherwise be sidelined as mundane.

Being a 14th generation Edokko, (then name for Tokyo) it was impossible for Hasegawa to imagine his ancestors living in Japan in the 1970s when industrialization was at its peak and the photochemical smog prevented even the sight of the moon. The decision to live a life in harmony with nature, made Hasegawa shift away from the city and retreat into the snowy forest region of Tokamachi. He converted an elementary school into a center for facilitating spiritual and cultural learnings and dialogue. It was here that he met a visitor, who had returned from a trip to India along with the work of Smt. Ganga Devi. The work fascinated Hasegawa, and he visited India in search of Ganga Devi and Madhubani art in general.

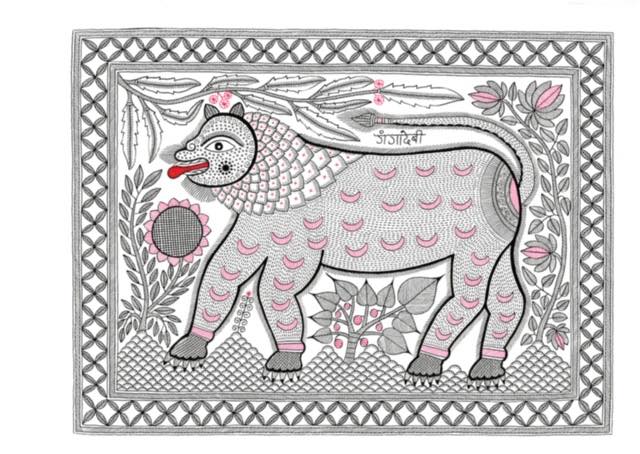

Lion Eating the Moon by Smt Ganga Devi

Seeing Ganga Devi’s simple living, her unflinching faith, and devotion and its manifestation in her art, Hasegawa felt a connection between Madhubani art and cosmology. For him, it was an offering to the divine. However, it also made him realize that the increasing western cultural influence at that time, risked the sustainability of traditional art forms, and so he decided to open a museum dedicated to the preservation of Madhubani paintings. He told us that “while the Meiji era had prevented the colonization of Japan by the Western powers, the opening of economies led to the inflow of western cultural influence and aspirations of “modernization” in the Japanese society. We have replaced Kimono with denim for comfort, for example”.

In a similar fashion, “Madhubani reminded me of the fate of Ukio-e, a Japanese art that dissipated with modernization and influence of western schools of art coming in. I wanted to protect Madhubani and this motivated me to open the museum,” he said. The Mithila Museum was finally inaugurated in 1982. Since then, the site has been regarded as a benchmark of India-Japan cultural heritage and enabled art exchange programmes for artists from across India.

These efforts of preserving Madhubani and other Indian art forms, therefore, falls within the larger ambit of exposing the Japanese society, and the global audience at large, to the “Eastern” cultures. Creativity has always been Hasegawa’s forte, and he describes himself as an Avant-Garde musician, who sought to lace eastern philosophies with New Jazz. He told us about traditional Japanese music, and also gave a flavour of the various sounds in the most candid manner. Hasegawa drew parallels between the Japanese art form Jyoururi–a theatrical performance with songs and accompanied by the Shamisen, that expressed the sentiments, scenes and meaning of Kabuki performance in a deeply emotional way–and Dhrupad, a form of Indian classical music. He understands the complexities in understanding the depth of classical music, especially by the younger generations who are more drawn towards western music, but at the same time feels that traditional music cannot be replaced to express sentiments of the land.

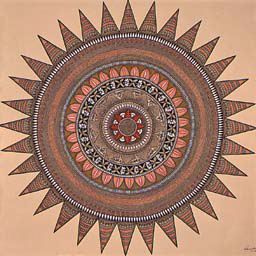

Chakra by Smt. Godawari Datta

An exponent of classical arts and traditions, Hasegawa has been at the forefront of the Namaste India festival, taking it from Tokyo to even the innermost regions of Japan. He channelizes his energies and capital in the preservation of art and artists, and believes that Ganga Devi should be acclaimed as the ‘Picasso of the East’. While this thought excites him, and we could see the glee in his eyes, he also conveyed dismay about the fact that the newer generation of Madhubani artists are moving away from cosmological works of art. One could only hope that the legacy of Ganga Devi and many other brilliant Indian artists continues.

Image Credits: Mithila Museum

Article co-authored by Aparna Sridhar and Arunima Gupta