The Natya Shastra of Bharata Muni is the fountain head of Indian dramatics, dance and music. Performance theorist Richard Schechner, comparing the Natya Shastra to the Poetics by Aristotle, says both occupy parallel positions in Indian and European performance theory, and are at or near the ‘origins’ of their respective performance traditions.

The two however are quite different, he adds. While the Poetics is focussed on the structure of drama and dependent on logical thinking, the Natya Shastra is a sastra, a sacred text full of narration, myth, and detailed instruction for performers. “The Natya Shastra is much more powerful as an embodied set of ideas and practices than as a written text. Unlike the Poetics, the NS is more danced than read.”

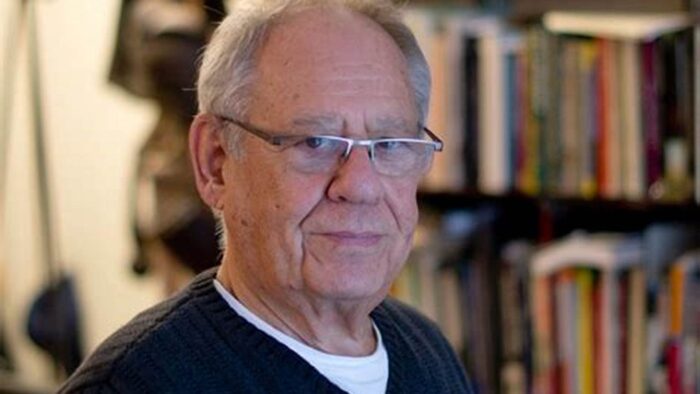

CSP in an interview with Richard Schechner (https://youtu.be/sTivSnylpMg) explored his journey to India and the influence of the Indian performance traditions on his work and life.

Richard Schechner, who is the Editor of The Drama Review, first visited India in 1970, nearly 50 years ago. At the end of one of his performances of Environmental theatre (a branch of the New Theatre movement of the 1960s that aimed to heighten audience awareness of theatre by eliminating the distinction between the audience’s and the actors’ space) a person came up to him and said, “It's clear from your performance that you've studied or been to Asia.” No, said Schechner. The person was Porter McRae of the John D Rockefeller Foundation, which later became the Asian Cultural Council, a major funder of scholarly visits to Asia.

The foundation subsidised a six month long trip to Asia for Schechner, the first four months of which were spent in India. After India, he also went to Japan, Indonesia, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand and also Papua New Guinea and Australia. It was 1971, and Schechner was in his 30s. He was already a professor, as well as a theater director and was introduced to Suresh Avasthi, the Secretary of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, who asked him what he was interested in. Schechner told him he was not interested in Western theatre as it was practised in India. “I didn’t even like Western theatre as it was practised in the west. But what I was interested in was Indian performance.”

Speaking on the differences between Western and Indian theatre, at places like the National School of Drama, what is being taught, Schechner says, is a kind of Indian theatre that is largely derived from western modes of performance, that is playwright stagings on proscenium stages. He doesn't think that there isn't an easily distinguishable category such as Western theater or Indian theatre; there are all sorts. But if you are talking about dances, certain Indian dances are termed Indian classical, such as Bharatanatyam, and certain music is termed Carnatic, some Hindustani. But they are all formed by the same principle of notes and scales, and so is Western music, and while obviously the structure is very different, the fundamentals are the same, and he believes the same is true of all fields of art.

Avasti had many contacts, and he gave Schechner letters of introductions or made phone calls, so that Schechner got to see many, many different forms of performance all over India, from Yakshagana, Kathakali, to Kallaripayattu, to Bharathnatyam, Odissi and Kathak. Deciding to settle down for a while, Schechner stayed in Madras, living with a family that had a house in Shastri Nagar near Kalakshetra. Here, he saw Bala Saraswati dance for the first time, a great experience for him.

Bala Saraswati was in her 50s at the time and was depicting the scene where Yashoda asks Krishna to take the dirt out of his mouth. “It was fabulously performed. She falls back when she sees what was in her baby’s mouth. He asks her ‘tell me what I can give you’ and she says ‘take away this memory that this thing has ever happened, because if I know who you are, you cannot be my baby anymore. You will be the Lord.’ It was just breathtaking,” says Schechner.

He watched some of the training in Bharatanatyam, but also began to study yoga with Krishnamacharya, who took a liking to him and took him on as a private pupil. Schechner admired him greatly and later, would teach yoga himself, not as a yoga teacher but as part of his performance training.

Schechner says he now does yoga and some modified Pilates, and is not bothered overly by consistency or purity. He does what he was taught to the best of his abilities. While he used to be able to stand on his head and do a full lotus position and raise up and down, he can’t do that now at 86, but he says that makes his yoga practice different, but not less. He does not want to think of what he no longer has, because that would take away the flavour of the life he is living. “One must enjoy the food that is on your plate, not what used to be on your plate. If not you will tend to keep thinking of what you cannot do or do not have anymore, which would just lead to an unadvisable state of despair.”

Schechner also brought his own production of Bertolt Brecht's Mother Courage and Her Children on his second trip to India, performed in Delhi, Lucknow and a small village outside Calcutta. It was not a proscenium based performance, with a stage and audience facing it, but his own style of environmental theatre. After that tour of about a month and a half, Schechner went for the summer to live in Cheruthuruthy, the seat of the Kathakali Kalamandalam, and it was here that he first really read the Natya Shastra, and also studied some Kathakali. He was around 42 years old, but said he wanted to take the introductory training like the eight year old boys, declining their offer of a special teacher. Despite their occasionally laughing at him, Schechner had a good time, and he was also simultaneously reading the Natya Shastra. The book deeply affected him, especially the part about rasa.

“My experiences in Asia have helped me grasp the creative process differently than I had when I knew only Euro-American theater. I have come to know the body as the source of theatrical thought as well as a means of expression. I experienced a confluence of theater, dance, and music: they became transformed into the consciousness of action, movement, and sound. I felt, as Suzuki does, that "the word is an act of the body" (1982, 89). And I know what Phillip Zarrilli means when he reflects upon changes wrought in his being through training in Kalarippayatt, a Kerala martial art closely related to Kathakali training,” writes Schechner of his experiences.

He adds: “What impressed me most about the methods at the Kalamandalam was the insistence — not spoken or theorized but omnipresent nevertheless — that the body comes first, that performance knowledge enters a person by means of rigorous, continuous, rhythmical bodywork. On 6 July I joined the class of young boys. Immediately after, I noted: Felt very good. Much easier to do when there are others doing it too. Much easier both mentally and physically. But at the same time the work is harder — more strenuous — than when I was doing it alone, or with only my teacher. This morning sweat rivered my face and torso. Instead of asking "What's next?" I just went with the others. My eyes saw, my body did. No translation; just eyes to muscles.”

After that, Schechner began a serious study of the Ram Leela of Ramnagar. Every year, during the festive season, Ramnagar in Varanasi breaks from the present and steps back 200 years. Led by the erstwhile ‘maharaja’ of Banaras, the town hosts a 31-day Ramnagar ki Ramlila, in which the entire epic plays out almost in real time in localities with names such as Lanka, Ashok Vatika and Ayodhya, and around a pond called Ganga.

Sri Ram: Photograph by Richard Schechner

Lakshmana: Photograph by Richard Schechner

The Ramlila was started by Maharaja Udit Narayan Singh in 1830, and its organisers pride themselves on the fact that it has never been disrupted — through battles and wars, famines and droughts, and change in regimes.

Schechner has written a lot about the Ram Leela, and also on Benares and Kashi. He met the Maharaja, who allowed him to take photographs. He has the world's largest archive of Ram Leela photographs, not open to the public, although he has published some.

The Ram Leela is India’s largest moving dramatic performance, where the Ram Charit Manas of Tulsidas is read at a temple in Janakapuri, the paternal home of Sita. “While the language of Tulsidas was not the Hindi spoken by common people on the streets, some variations had Lord Rama and his brothers speaking in the common Hindi of that part of Uttar Pradesh,” observes Schechner.

Coronation scene: Photographs by Richard Schechner

Coronation scene: Photographs by Richard Schechner

Schechner is an initiated Hindu Brahmin having undergone the rites and thread ceremony and was named Jaya Ganesh. He was not asked to give up his Judaism, he says, identifying himself by both faiths. “My decision was made partly because I wished to be able to witness the inner sanctums of the temples nearby, and partly because of curiosity and real belief.”

Rasa

Schechner finds that most artists all over the world, including the West, are not particularly theoretically inclined, save a few. And teachers, he says, teach more along the mythic lines of theory, not the critical lines of theory.

Quoting the Natya Shastra, Schecner says:

There is no natya without rasa. Rasa is the cumulative result of vibhava (stimulus), anubhava (involuntary reaction) and vyabhicari bhava (voluntary reaction).

Speaking about rasa, Schechner says it is a metaphor of juice or flavour, and is very much like food, in that one can enjoy food without being a great connoisseur of it. One can have a fuller appreciation of something the more one knows, but that does not mean the enjoyment does not exist even with ignorance about the detail. So somebody at a very low level of knowledge may actually very much love an Odissi dancer.

He quotes the Natya Shastra “Those who are connoisseurs (bhaktas) of tastes enjoy the taste of food prepared from (or containing) different stuff; likewise, intelligent, healthy persons enjoy various sthayi bhavas related to the acting of emotions (Bharatamuni).

Schechner says the sthayi bhavas are the “permanent” or “abiding” or indwelling emotions that are accessed and evoked by good acting, called abhinaya. Rasa is experiencing the sthayi bhavas. To put it another way, the sweetness “in” a plum is its sthayi bhava, the experience of “tasting the sweet” is rasa. The means of getting the taste across - preparing it, presenting it - abhinaya.”

At the artistic level, Schechner says that the transmission of a tradition is always constrained by what the student takes from the art, because one cannot imitate exactly, even if a traditionalist will always say the art form never changes. Historically, Schechner says, we can see it does change. “Speaking of the Natya Shastra itself, there were eight rasas in Bharata’s book, but now there are nine.”

When asked to describe Shanta, the ninth rasa, Schechner says to think of a rainbow, which has many colours - the rasas, but when combined in the perfect balance, they all disappear. Experiencing the basic rasas in harmony leads to Shanta. Light has no colour till it is refracted, but it is a combination of many colours.

Rasa Box exercise with Shanta in the centre

As an artist, Schechner was fascinated by this. He did the rasa boxes exercise and was fascinated by a non-Stanislavsky approach towards emotion. He says rasa boxes could be used to analyse texts and emotion, for example, Romeo and Juliet. Usually, people would say Juliet’s basic rasa is shringara because she's driven by love. But maybe it's Roudra, Schechner says, because she is furious at being restricted by her parents and she does not really love Romeo, but wants to get away from her parents. He asks the performer to think about which is the primary rasa driving the character, with layering. Classical Indian actors have their own set of abhinayas. But actors can use the primary rasa and layer it with another rasa, like vanilla flavouring with chocolate cream on top. The best way to learn about rasa boxes is to practice it and attend the workshops.

Michele Minnick, a student of Schechner, in his article Rasaboxes Performer Training tells us how Rasa boxes work. “The key to their design is the spacialisation of emotions. What makes our use of rasa ‘Western’ is that rather than codifying the expression of emotion through particular genres and facial expressions that are always performed in the same way (as in classical Indian dance), we use space to delineate each rasa, and allow the individual performer to find her own expression of the emotion/s contained within it.”

“The first step towards movement improvisation involves getting into one box at a time and creating a ‘statue’ or fixed pose for each rasa. We then establish that a participant cannot be in a Rasabox without expressing it dynamically. Participants then move among the rasas, embodying each rasa by means of the pose they have chosen. The idea is to move from one box to another with no ‘daylight’ - no period of transition- between them. This develops an emotional/physical agility the actor can use to transform instantly from expressing rage to love to sadness to disgust, etc. Once participants are comfortable being statues, we introduce breath and then sound and finally movement and sound together. What starts as a fairly controlled exercise develops into a very free improvisation, involving a range of interactions or “scenes” between different people in different boxes.”

It is not necessary to experience the rasa while acting, but it must be expressed accurately. In the theatre of the Ram Lila, the young boy, when he is playing Ram and wearing the crown he is Ram. Schechner also speaks of how while the brothers are all born on the same day, Ram must always be the tallest because it is the logic of performance, and the narrative, which is why imagery is powerful. Schechner brings in the concept of Maya and Leela, how everything is an illusion, and is play. He believes that the notion of Maya Leela is powerful for artists, because it asserts that the play, the imaginary, is a Maya Leela of a Maya Leela, an enhanced version of the actual Maya Leela.

Schechner says learning about the arts is subjective, you can have a swift deep experience or spend years and never get anything from it; you can learn the mechanics but not the rasa. He believes that people must learn about other cultures, their art, perform other cultures, so as to stretch boundaries and understand possibilities.

In other words, the paradox of being human, Schechner says, is that by origin, we all came from one or two places, but branches of the tree have spread very far, even though they arise from the same trunk. “One should have cultural experiences that are different than the ones you were brought up with, so that would remind you of the fabulous truth of human existence, that we are different but all the same, genetically extremely close but culturally so diverse, and these differences have been sometimes in a great pleasurable way celebrated. Experiencing other cultures through performance arts reminds one both of the beauty of the similarities and that of the differences.”