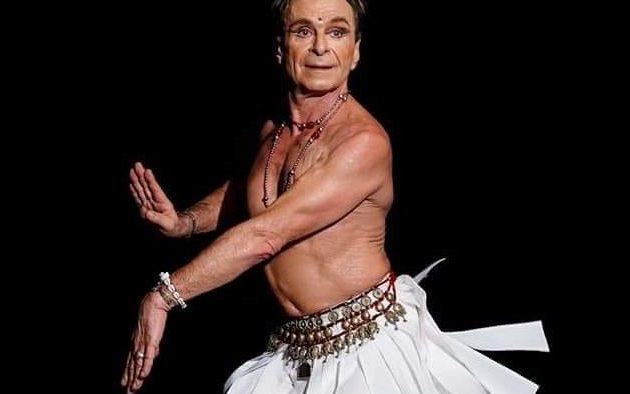

French dancer Dominique Delorme built his house in France from foundation to roof with his own hands. Something that gave him deep satisfaction, but caused an injury which forced him to postpone his performance at the Chennai Music Academy by a year, to 2011. It took him seven years to build his house, which meant years spent away from India, away from his gurus and the sacred spaces in which his dance had been shaped.

But it provided him the quiet needed after two decades of hectic activity. His training in India was eclectic involving all aspects of dance, but a lot of it was transmitted without words. “Almost all the aspects of dance, theatre and music fall in this category. To learn one needs to be in silence with one self. Whatever you want to fill in has to be empty. Natyashastra mentions four types of abhinaya (ways of communication): angika (through body), vaacika (through speech), ahaarya (through external elements, costumes, props, etc) and saatvika (communication of the deep self). The first three abhinayas can be taught, saatvika cannot, it has to be felt from the interpreter. Whatever the subject, my Indian masters talked as less as possible during the class. Let's not forget that God teaches in silence,” says Dominique.

He has a simple axiom, “Whatever the style you want to learn, wherever you are on the planet, work hard, with conviction, with dedication. If you want to reach higher standards, choose a great guru (guide), in whom you have trust and from whom you get inspiration. Tradition contains fundamental values. One has to be deeply rooted in a tradition before one tries to develop it. I have developed movements on my own but they are rooted in what I have been taught.”

A soul-searching trip to India in 1983 led to his learning from Christine Klein (whose stage name is Malavika), a Paris based Bharatanatyam dancer. Malavika herself started at a very young age and was part of Ram Gopal's company as a young girl. When she became a teenager, she was brought and left by her parents to study Bharatanatyam under Guru Kancheepuram Ellappa Mudaliar. “Back in Paris, she was a kind of pioneer of Indian classical dance and trained numerous dancers; most of them learnt later on with guru V S Muthuswamy Pillai. After my studies in Chennai and when I returned back to France, we created several dance duets together which were staged by her sister Nita Klein and toured India. Today, at the age of 80 plus, she is still performing and carrying on Indian classical dance and spirit.”

Dominique had wanted to be a surgeon from early childhood. But when he started his dance training at 22, he immediately realised that there was no time to loose and from the beginning started heavy practice daily. “This regime has been going on since that time. Forget that you are tired or not well. Dance, and you will feel better! From morning till evening, I am always connected with dance. Dance starts with the movement of your eyelids opening, continues in the way you walk and finishes the moment you close your eyelids. In fact, even after closing my eyelids, I visualise choreographies. It never ends. There are even nights where I dream I am flying. What an extraordinary feeling!”

When he came to study in Chennai in 1987, he felt the importance of learning music and rhythmics as well. “Indian classical dance is a complete art form. If you want to be a complete artist, you have to study all its aspects. I had my music training from Smt Sulochanna Pattabhiraman and my nattuvangam training from Smt Kamala Rani of Kalakshetra, who was Rukmini Devi's nattuvannar. Both of them knew that my main subject was dance but with affection and discipline, they made sure that I got strong basics in Carnatic vocal music and nattuvangam.”

In 1987, he began his training under V S Muthuswamy Pillai in Chennai, simultaneously training in ‘abhinaya’ from Kalanidhi Narayanan and Anuradha Jagannathan.

When he came to Muthuswamy Pillai, the guru had been waiting for a male student for 25 years. “He is one of the rare nattuvanars who had danced himself (dressed as a girl, at that time!). I do not know exactly why he was so keen on teaching a boy but what I know is that we had a very deep understanding from a guru to a shishya. He wanted perfection and I was ready to give him my best. I met him at the end of his life and his imagination in matters of creating new adavus and new choreographies was unlimited. I was there to fulfil in dance what he had in his creative mind.”

Asked about the mandi adavus composed exclusively for Dominique, he says, “He was using the mandi adavus a lot in my choreographies. He told me that female dancers do not have enough stamina for that. He trained me in 13 families of adavus and all together, I had about 500 varieties. Even at that time, my colleague dancers, learning in other Bharatanatyam styles had merely 50 or 60. To me, it was always a great pleasure to work with him on adavus. It was not only learning dance steps, it was already conceiving them in space, using diagonals and back movements, which was entirely new at that time. I heard that nowadays, dance students learn choreographies without going through the adavus. What a mistake! This is not the way I teach. If you want to give respect to a style, to the masters who learnt from their masters, teach your students the basics of that style. Then only they will grow. Without roots, a tree will not give you flowers and fruits.”

His training took a new direction in 1989, when he met Padma Subrahmanyam and started training in the Bharatanrityam style. What he learnt took expression in his role of Shiva in ‘Natya Shastra Avataranam’ (1990) choreographed by Padma Subrahmanyam and the role of Narada in ‘Krishnam Vande Jagathgurum’ (1991) choreographed by Sudharani Raghupathy on a Spic Macay tour.

Dominique says today his students abroad prefer Bharatanrtyam to Bharatanatyam because “the style is more fluid and more expressive. It also has more variety of movements and many of them are similar to those used in the western dance styles. However, whether traditional or contemporary, an audience is convinced when it gets rasa. It all depends on the artist's bhava!”

In 1991, he was invited with his guru Muthuswamy Pillai to perform at the International dance festival of Montpellier and danced in Shakuntala’s choreography 'Seeds of Light' at Theater de la Bastille in Paris. He also featured in the 13 episodes documentary film 'Bharatiya Natya Shastra' on Padma Subrahmanyam’s research, directed by V. Balakrishnan for DD.

Everything spins around the Natyashastra. “Natyashastra is the root to any dance, theatre and music student in India. It has influenced these arts in the whole South Indian continent, from Afghanistan to Indonesia, and beyond in Cambodia, Thailand, Burma. All the Indian dance styles have developed from certain aspects of the Natyashastra.”

So at what stage does a student immerse himself in it. “It is always preferable to start dance at an early age because one learns quickly. But with hard work and conviction one can start later on. Whatever the age, there is always something to learn from Natyashastra. A dancer who has learnt an Indian style will automatically find connections between his style and the Natyashastra,” says Dominque.

He hit his stride in 1994, with his first solo production ‘Nandanar’ which received critical acclaim and became one of his masterpieces which toured India, Europe and the USA.

He had choregraphed ‘Nandanar’ in 1994 in Vienna (Austria), when he returned to Europe after many years of studies and performances in India. “Coming back to Europe, I felt that the traditional Bharatanatyam repertoire was difficult to be perceived by a western audience. Therefore I decided to create a thematic performance to adapt Indian classical dance to the imaginary of a western audience. I chose Nandanar for different reasons. The first one is because I had learnt several padams from Smt Kalanidhy Narayanan on Nandanar Charitram. The second one is because Nandanar was a farmer and I am born in a farmer's family; it must have helped me to identify with this character. The third one is because I was deeply touched by the humility of the character. The fourth reason but not the last, is the spiritual message contained in Nandanar's story: an outcast reached a saint level in one life span,” says Dominique.

He had danced Nandanar in Chennai when Padma Subrahmanyam was not in town. When she saw it she arranged for performances in temples of Nagapatnam and other big temples.

Dominique is happy that dances are being performed in temples today once again. “For centuries, Indian temples have been connecting people with the arts of dance and music. During the 20th century, dance left the temples and came on stages. I am personally happy that it makes a come back to the temples. I performed for Natyanjalis in several temples and each time it was a great experience. The feeling that, in the past, dancers have been stamping the same temple floors... When Padma Subrahmanyam saw my choreography of Nandanar, she organised my performance in several temples of Tamizh Nadu and told me: Go and perform Nandanar for the villagers in those temples, there you can never get a better audience for such a character. Once again, she was true!”

His other production 'Karana', a solo production based on his research with Padma Subhramanyam on ancient Indian dance, toured the world for over a decade. “She recreated the karana movements from the sculptures, the Natyashastra and its commentaries, especially those from Abhinava Gupta (Cashemire 11th century). It has been a lifelong work studying the karana sculptures along with the text. She must have had a deep intuition of these movements. I personally believe it is a karmic situation, in the sense that she must have performed them in previous lives; if not she might be a reincarnation of Bharata himself!"

Dominique has danced the 108 karanas at 42 degrees. This was just before he had to leave for France in 2001. In an interview to Sacred Space he has said, “It was 42 degrees, the height of summer, and the performance was in an open-air auditorium. And that day I really thought I was going to die. No one had performed the 108 karanas before! At a certain point during the performance, I heard a voice from the wings calling: “Dominique, come!” So during a karana I walked out to the wings, and she (Padma S) put a towel on my face and poured a bottle of glucose water in my mouth and said, "Go!", and I finished the karanas. I danced them continuously. It takes 45 minutes but it’s like doing 3 varnams in one go because you have no sahitya, it’s only nritta. And afterwards her brother told her, “Padma you should never do something like that. We don’t know what it’s like to perform all the karanas!” So they told me that if I ever do it in France, I should split it in two or three parts, and not do it in one go. Plus it was 42 degrees! It was mad.”

Dominique lived in India for 10 years but had to leave as he had come to study with the help of a scholarship from the French and Indian governments. “When I finished my studies, I wanted to stay in Chennai. Guru Muthuswamy Pillai had passed away and the dance field in Chennai helped me to stay so that I continue teaching his style. Later on, the French Government gently asked me to come back to France since I had signed a paper mentioning that after my studies I would return to France and transmit what I had learnt. Unfortunately I had to leave, but honestly, it was hard!”

The scholarship had been instrumental in his coming to India. “I come from a very modest farmer’s family and without the scholarships I couldn't have stayed so long in Chennai to do my studies. I wanted to learn dance but I felt the necessity to learn theatre, music and nattuvangam. I also took yoga, Tamizh and Sanskrit lessons. All these subjects need a lot of time. Indian classical dance and music are not fast food, they require patience, humility and hard work. More than that, foreign students need to soak in Indian culture, to be exposed to the temple rituals, to feel the atmosphere of India and all what makes the spirit of India. I am sincerely thankful to the French and Indian governments for having given me the opportunity to stay all these years in India to make serious and in-depth studies. Unfortunately the Indo French government's scholarships are no more given for artistic students. That's a huge pity and I wish that will be repaired in future,” says Dominique.

The sacred is clearly important to Dominique. “Soulful art can be found in many parts of the world. One of my last choreographies makes a link between the sacred in Indian classical dance and the dervishes in the Sufi tradition. I have performed with chamanic South Korean musicians and the sacred is a fundamental of their tradition. The sacred happens when the interpreter is deeply involved in the situation, whether as a dancer, an actor, a musician, a painter, a sculptor, a human being."

Finally, about Nataraja - the Lord of Dance, Dominque says “He is perfection incarnated and the One to whom I address my prayers daily and whenever I dance. He is the perfection which I try to reach in my practice and my spiritual path. The more I dance, the humbler I feel. In this life, that perfection seems to be out of reach. I might need a few more lives...