Archaeologist John M Fritz visits Hampi every New Year and likes to meet his friend Krishnadevaraya, the descendant of the famous ruler of the Vijayanagara empire who lives in Anegundi near Hampi. He will be happy to learn that soon a 215 feet statue of his favourite deity Hanuman will come up in Hampi, erstwhile Kishkinda.

Fritz remembers his first walk around Hampi with the eminent historian George Michell. They walked for almost a mile, and he was shown the structures, the walls, tombs and temples. “It was beautiful. The whole landscape, the giant boulders and the sparse vegetation had a raw beauty,” says Fritz.

Ofcourse, Michell and Fritz were looking through different eyes. “George was interested in what was standing and I was interested in what had fallen!”

He had been studying archaeology at Chicago University and had taken up work as Adjunct Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Mexico to study Chaco sites. The sites were a network of archaeological spaces in north-western New Mexico which preserve the elements of a vast pre-Columbian cultural complex that dominated south western United States from mid-9th to early 13th centuries.

For John, archaeology is a metaphor for the relations between society, nature and the sacred. He was among the first to analyse and embed meaning in architecture and archaeological spaces.

Little did the world know that this expert on Chaco sites, which are remarkably like Hampi, would unravel the mystery and grandeur of the Vijayanagara empire through his study of the ruins and structures at Hampi.

Meanwhile in India, George Michell, a London based architectural historian, had begun work at the Hampi site with a small group of architecture students, and John Gollings, an Australian architectural photographer. They had joined scholar couple Dr Vasundhara Filliozat and Dr Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat, who were investigating the inscriptions at the famous Vitthala temple.

Michell felt the need for proper documentation of the thousands of years of findings. And that is when he met Fritz. Michel and Fritz were to providentially cross paths at London, where Fritz was presenting a paper about his work on the Layout of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, at the conference titled “Symbolic and Structural Archaeology” at Cambridge University. The preliminary drawings and photographs which Michell showed Fritz, convinced him to provide the archaeological support and he stepped in to survey, draw, correct and finally catalogue Hampi. He joined as co-director of the team and co-founder of the Vijayanagara Research Project (VRP) with the intention of mapping the area thoroughly.

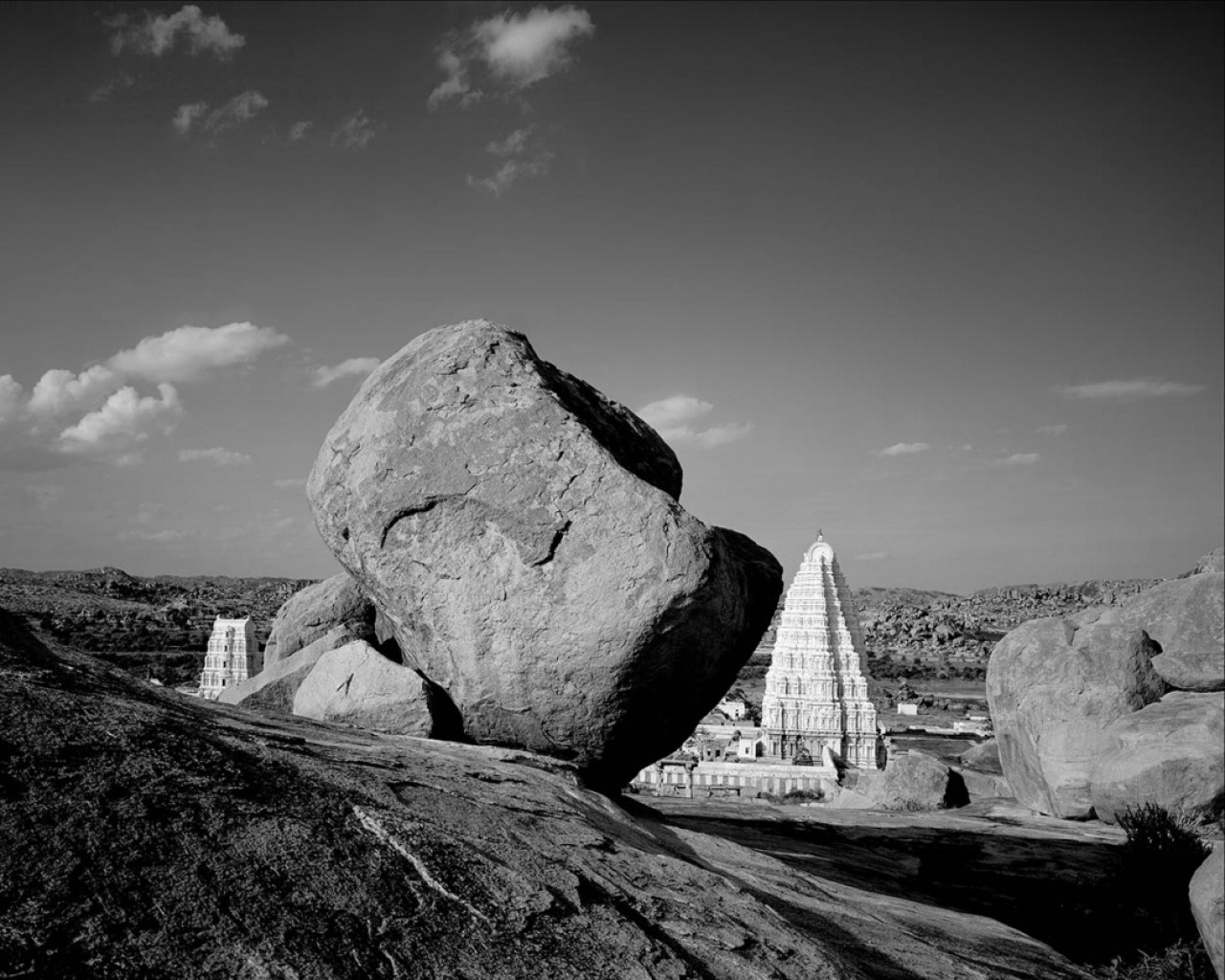

Currently, Michell and Fritz are editing the maps of the splendid Virupaksha temple, correcting the markings on the map for inscriptions, pillars, carvings and all the architectural details. Despite the fact that VPR wound up in 2011 they are still consumed by Hampi.

Virupaksha Temple, Hampi. (Pic courtesy: John Golling)

In an informal chat with CSP, Fritz visits the heady days of VRP and shares his insights and anecdotes.

What is the connection of Vijayanagara with India’s greatest Ithihasa - the Ramayana, as you are familiar with the Ramayana and especially the Kishkinda khanda?

It was brilliant move on the part of the Rayas to bring Ramayana inside the royal quarters merging the sacred and the royal. This is the Ramayana territory. Kishkinda is where the action happens. In the sacred land of Virupaksha, the kings established themselves as Rama incarnate and built their personal temple Hazara Rama. The ideal king ruling with Rama’s grace - no wonder it became Vijayanagara - city of Victory unparalleled in its arts, riches, culture in the medieval world to which flocked the scholars, traders, performers from all corners of the world.

Hanuman temple on the Hemakuta Hill, Hampi. (Pic courtesy John Gollings)

What fascinated you about Hampi initially?

I was interested in cultural archaeology. I do not subscribe to traditional British archaeology that is based on study of monuments. I was fascinated and intrigued by the pictures that George showed. In the preliminary drawings of George, I could see evidence of conscious planning on a large scale. The information on the city’s urban centre convinced me that it could be studied based on direct and easy observation. The temples were cardinally aligned. I also saw that some civic structures and surrounding rectilinear compound walls, were similarly aligned. All of this intrigued me.

In the drawings of George, I had seen buildings in every state of preservation and the remains of otherwise vanished structures in between the monuments. These impressions were confirmed when I first saw the site in January, 1981.

During that month I was introduced to the core area by George, Vasundhara and Pierre-Sylvian Filliozat (epigraphist and Sanskritist) and John Gollings (photographer) all of whom had participated in the 1980 season.

What is your favourite part of Vijayanagara?

The Royal centre. It is the first well-preserved palace zone in South India. We read about the grandeur of the Cholas and Kakatiyas, but apart from the sacred site we have no evidence of royal life. At Hampi we see the nobility living in splendour with baths, wide streets, guard towers, royal temple and my personal favourite the Mahanavami dibba.

Analysing the sculptures on the Dibba we can construct the evolution of Vijayanagara Empire. At the lower tier are sculptures of general interest whereas the upper ones are of erotic nature, carved in perfection, signifying the distance between the royalty and the subjects signifying that it was more of a private space to which only the closest got an invitation.

Can you take us through the early days of Hampi’s restoration?

By the beginning of the 20th century Hampi had ignited the interest of historians. Work at Vijayanagara accelerated in the late 1970s under a National Project. It had stimulated further clearing work and extensive excavation of the palace area by central and state archaeologists. The newly formed ASI had uncovered and conserved certain monuments at Hampi. By 1980, the ASI and KDAM were excavating in what we came to call the Royal Center of Vijayanagara. These activities were fully under way when the Vijayanagara Research Project first began work at the site in 1980, to map and document the site to investigate, interpret and to offer essential background information on the history of the city and the empire of which it was the capital, the urban layout of the site, and the variety of its military, ceremonial, civic and religious architecture.

VRP worked under the direction of the ASI and the Karnataka Government Directorate of Archaeology and Museums till it was wound up in 1990, drawing funds from numerous international organisations, grants from governments and intellectual support from scholars all over the world. A global project the like which was rarely seen in this part of the world.

George Michell at work at the camp in Hampi (Photo Courtesy: Surendra Kumar)

How did the momentum build up for the interest in your project?

George and I participated in academic conferences and lectured frequently at universities in India, Australia, the UK and the US, thereby maintained on-going interest in the Project and a seemingly inexhaustible stream of volunteer contributors. A steady stream of scholars, volunteers, students joined the project year after year.

In the initial days there were hardly any funds. Yet, scholars from all parts of the world came to be a part of something worthwhile. Many returned season after season because “They were won over by the magic of Hampi.” Dr Anila Verghese not only wrote books on Hampi but also brought her students to experience archaeology first hand.

What was the most ‘archeologically’ exciting discovery about the Vijayanagara site?

One of the most exciting aspects of the Vijayanagara site when we began to document it at the beginning of the 1980’s, was the apparent excellent preservation of its archaeological record. In addition to some identifiable 1,000 structures standing or ruined, we observed eroding walls, abandoned roads and hydraulic works and -- carved into sheet rock and boulders -- many types of facilities (mortars, ties) as well as game boards, sculptures and inscriptions. So, we conceived a program of “surface archaeology” which would encompass non-invasive techniques of documentation drawn from architecture and archaeology.

Since it does not involve intensive labour, surface archaeology is more rapid and can cover extensive areas with a wide variety of characteristics. Since destructive techniques were not used; there was a greater freedom regarding what was to be documented and the intensity of its documentation.

John Fritz

John Fritz

What did the excavation and documentation include?

Our team studied the religious and the royal monuments. In addition, we examined the planning of the city, the extensive military fortifications, a complex hydraulic system, and even traces of the lives of common people. It was most fascinating to study the relationship of Vijayanagara’s layout to features in the surrounding landscape. Some of these features had long been identified with episodes in the Ramayana. We came to understand that associations between Vijayanagara’s rulers, the gods, and the city’s natural setting were keys to understanding how three successive lines of rulers commanded a kingdom that grew into an empire.

The work of VPR can be categorised under two headings: Mapping and survey of the site and documenting it intensely and the interpretation by scholars.

In terms of mapping, VPR did a comprehensive documenting of site - the sum total of material life in medieval Vijayanagara .The outcome of which is the Vijayanagara Archaeological Atlas. Along with the architectural drawing of well-preserved buildings, we decided to document the form, location and topographic context of cultural features. We would record rock-cut as well as ruined and preserved structural features using surveyed maps, drawings, photographs, key words and written descriptions. It became necessary to examine each map and feature and to record it meticulously, edit them as necessary so as to ensure that they are consistent, intelligible and error free. The Vijayanagara Archaeological Atlas (VAA) is the product of this work. This work is being carried out by me and Surendra Kumar.

The British Library has graciously agreed to house many documents produced during our work, including, maps, drawings and photographs. These will join the Library’s important archive of southern Indian records held in its British Library Asia Pacific & Africa Collections and it is available to anyone for reference open source.

Along with the documenting of the archaeological site, VRP invited scholars from various disciplines, oral history traditions, specialists in scriptures, archaeon-astronomy, ethnoarchaeology , geoarchaeology, for the interpretation of the archaeological records.

The sacred, the profound and the profane were each written about by scholars like Dr Anna L Dallapicolla, Dr Anila Verghese, Dr Karla Simpoli, Dr Asim Krsna Das, C.T.M. Kotraiah, Dr Dominic Davison-Jenkins, Prof. John McKim Malville, Dr Alexandra Mack, Prof. Ben Marsh and more.

What do you consider as your greatest contribution?

We are grateful to the scholars who believed in me and George and worked on VPR. Many of them went on to publish papers, attend conferences, write dissertations. A great many number of books were written on Hampi which have enhanced our understanding of one of the greatest empires of the Medieval world.

Today Hampi is one of the most important global tourist destinations and universities all over the world teach Hampi as part of their course on Archaeology.

In light of booming tourism, demands of the locals living on the site and quarrying how does one conserve a site like Hampi?

(Fritz was not very forthcoming on this because their voice is not heard. They were not consulted on any conservation measures.) If it was left to me, I would like the 25sq kms of the site to be declared a living, natural and archaeological heritage. A concerted effort on the part of government officials, temple committees, village leaders, agriculturists and leaders working in harmony can manage to preserve Vijayanagara’s extraordinary cultural resources for future generations… a tall order but if we pay heed that will be some victory, a victory for Vijayanagara indeed!

The Urban Core was opened up by VPR although the work had started earlier. It was opened at the request of the Karnataka government. It gives us a good idea about the crowded elite residential quarter. Shrines, palace complexes, rock-cut features, tombs, and the remains of many walls occur on hillocks. Earthenware ceramics are the most common surviving artefacts of the daily life of ordinary people; their houses, which were built of mud, bamboo and thatch, have mostly disappeared.

The broken pieces of Chinese blue-and-white porcelains indicate the districts inhabited by the courtly elite of the city. Almost no clearance work has taken place in this zone. However, temples dedicated to different Hindu cults, Jain temples and even two mosques indicate the diverse populations that once lived here. Even though there is no historical information yet we can get a sense of life of the elite.

Ken Juster US ambassador to India visited Hampi in December 2019 and spent spent hours at the site with George Michell and John Fritz at Hampi

What is the most accurate description of the Vijayanagara kingdom?

The Vijayanagara kingdom was much more than a Hindu kingdom or a regional kingdom. It supported Hindu faith and culture but at the same time it was one of the most cosmopolitan cities of the medieval world where all nationalities converged, where Muslima tombs are found in nobleman’s quarters, where the Vijayanagara emperors incorporated Muslim cultural practices when they borrowed sultanate modes of warfare and courtly ceremony and dress. Their attitude to architecture was no different. They adopted architectural features from the contemporary Sultans but creatively filtered the imported style through the lens of their own South Indian tradition. The result is a hybrid but inventive buildings of the Royal Centre. The sacred core remained Hindu in style and idiom but the secular innovated and evolved to establish the empire as the most cosmopolitan in the world where the bazars were lined with goods and buyers from everywhere.

(Cover pic by Vidya Viswanathan)