By Aparna Misra

Aesthetic sensibility, as Abhinavgupta says, is nothing but a capacity of wonder more elevated than the ordinary one. An opaque heart does not wonder: non obstupescit - Raniero Gnoli, paraphrasing Abhinavgupta

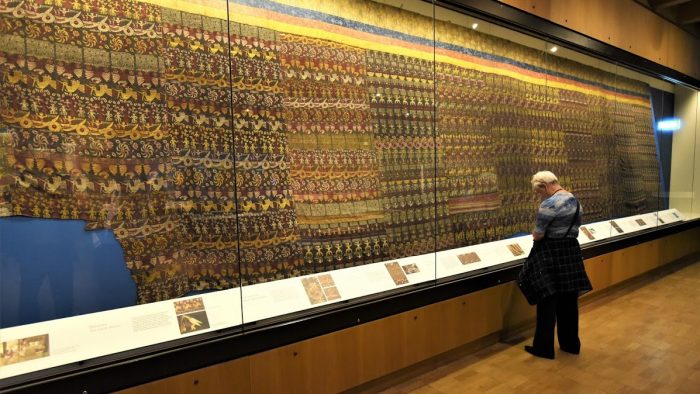

Vrindavani Vastra which was on display at the British Museum a while ago will move the opaquest of the hearts to ecstasy. You stand before it eyes wide open, gaping, mouth drooling (metaphorically), trying to identify the motifs stretched before your eyes…. is that a Bakasura, and over there is that a Kalia daman scene? Scenes look familiar and yet strange because you have never seen anything like this in your life….Ever! The tapestry before you is unsurpassed in beauty, unmatched in vibrancy and vigor in weaving the dramatic exploits of Krishna in warp and weft in a style called Lampa – the mother of all weaving styles!

You wrack your brains and wonder whether it can be called a craft or is it art most sublime only because you have read that weaving is classified as craft! But how can this chronicler of Krishna’s stay in Vrindavan woven in a style now extinct, in which every motif seems to jump out of its skein, be classified as craft?

For you the wonders never cease. You try to extrapolate about the traditions of the place, those weavers and their culture from where such a heavenly weave emerged. The label says Vrindavani Vastra but is it from Vrindavan? No! It is from Assam.

You are intrigued by its peripatetic history and wonder how did it find a permanent house in British Museum? It was once in a life time chance to witness this glorious weave in a Special Exhibit organized by the British Museum. The title of the special exhibit was – ‘Krishna in the Garden of Assam: The Cultural Context of an Indian Textile. Is it another tale of colonial appropriation? How did this gigantic woven celestial saga move across time space and cultures?

What tales does it hold? What is ‘Vrindavani Vastra’?

The beauty of the weave hypnotizes one. It is woven in the finest muga silk - in colours that still look radiant. It tells the story of Krishna’s stay in Vrindawan. Krishna spent the best part of his life in Vrindawan, hence the finest silk in brightest of colours were spun to weave the story of Madhava and his exploits.

Story behind the Vrindavani Vastra

India has a rich tradition of weaving. Each region has its own unique style. The grand weaves were meant either for the royalty or for the divinity. Most of the weaving towns grew around temples. But the piece displayed at the British Museum is no ordinary piece.

The story behind this divine weave needs to be told. It is unlikely that many in our part of the world would know about it. The British Museum displays not only a great textile but also a whole textile tradition, in fact — that came from Assam some 400 years or more ago. This ancient Assamese textile is over 9 meters long (length 937 centimeters and width 231 centimeters) and is the largest surviving example of this type of textile anywhere in the world

It is a piece the like of which you do not see now. It hangs in few museums around the globe. Those weavers and those times are gone. You try to speculate about those times, those weavers and the underlying faith that inspired men to weave an art so sublime that it transcends human limitations and makes it appear effortless and blessed!

Three things, if it can be simplified, were responsible for the creation of this heavenly weave; leadership of Srimanta Sankardeva, the socio-cultural factors of 16th century Assam and patronage by a transformed king.

Creative Forces behind the Vrindawani Vastra

The Vrindawani Vastra owes its exitence to one man – Srimanta Sanakardeva, born into the Shiromani (chief) Baro –Bhuyans family at Alipukhuri near Bordowa in 1499 in Assam. The Vastra had a key role to play played a key role in his scheme of his Eksaharana movement. If you try to contextualize Sanakardeva in the times in which he was born then you can understand the inevitability of this divine tapestry. He was born in fifteenth century. It was a time of conflict and churning. It was also a time of resurgence, revival of simple faith, simple literature and a direct connect with masses through bhakti. This was the time when saints like Nanak, Mirabai, Kabir, Ramananda, and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu were showing the path of bhakti.

Sankardeva was a child of these times. He craved for a simple faith, a simple religion that could heal the Assamese society torn apart by orthodoxy, sectarianism and fanaticism. In the course of his travels he witnessed the Bhakti movement sweeping across the country.

Sankardeva was a child of these times. He craved for a simple faith, a simple religion that could heal the Assamese society torn apart by orthodoxy, sectarianism and fanaticism. In the course of his travels he witnessed the Bhakti movement sweeping across the country.

His own inclination towards surrender to a personal God through sadhna and bhakti found resonance with the Neo- Vaishnavite movement. It is said that Jaganath Mishra’s narration of Bhagavatam at Puri opened his eyes to single minded devotion to Krishna. Sankardeva disapproved of idol worship. In the nomghars the focus of worship was Bhagvata Purana. Srimanta harnessed art for cause of spreading the message of Eksharana. A devotional song (borgeet) a spectacle of high melodrama (ankiya nat ) actors traversing the stage in masks, a homely verse for community chanting, a dance portraying the life of the Lord (sattriya ) would all become vehicles for propagation of his faith. Krishna was the sole worshipful, single minded refuge in him would lead to salvation and bliss. Ek sharana was Sanakardev’s dharma.

In the Nomgharas, the Vaishnavite silks were used to cover the manuscript and were draped over the altar on which the Bhagwata Purana was placed. This was the significance of Vaishnavite silk in Eksharna.

But the stunning display of Vaishnawite silk at the British Museum tells you in bold letters that this was not an ordinary altar peace.

Story of Royal Patronage

Any great piece of art is a product of unique factors of its time. It is also a reflection of those times. Vrindavani Vastra is a stellar example of leadership of Sankardeva and the society of his times and to what glories ordinary mortals are capable of when inspired! It immortalizes the king, the saint, the weavers of Tantikuchi and the spirit of bhakti that made this creation a possibility.

Katha Guru Charita, a chronicle of events during the saint's lifetime, gives the genesis of Vrindavan Vasta: It was woven at the behest of the King Narnarayan and his brother, Chairali. During his visits to the Koch Behar royal court, Sankaradeva often regaled Chilarai with descriptions of the fun-filled childhood days of the young Krishna in Vrindavan. The prince was enthralled, and wished he could partake of the experience. Sankaradeva replied that, for the prince's enjoyment, he would have the narrative inscribed on cloth in a graphic form if only the king could assure him of required quantity of silk yarns of different colour! The king used his royal prerogative, assured him of the supply and appointed Sankardeva as the Bar- Bhuyan (Chief Administer) of Tantikuchi.

Royal Scroll Commences

Sankardeva kept his promise Sankardeva himself supervised the weaving of the scroll. He conceived the design, worked out the pattern in different combinations and chose the weavers of Tantikuchi to translate the ambitious project in Lampa style of weaving.

Lampa is a very intricate style of weaving in which the base cloth is woven with one set of warp and weft threads, and a design is woven with another set of warp and weft.

Imagine a tapestry woven in finest silk – Muga; in brightest colours red, black, white, yellow and green, apart from the primary colours the colours were mixed; misravarna like kacha-nila, Gaura-syama to breathe life into Krihna’s lila at Vrindawan.

Sankaradeva used his knowledge of the Bhāgavata Purāna to weave the sequence of events of Krishna-lilā. His personal expertise as a painter, artist and dramatist made this Vastra an intensely personal communication.

The weaving of the Puranic tales on a gigantic tapestry 60 yards by 30 yards took almost a year to complete!

Sankardeva himself delivered the divine vastra to the court. When unveiled the royalty was astounded to see the true-to-life depictions of Krishna’s activities in Vrindavana the exuberant colours, in woven captions, and exclaimed that the cloth had come from the heavens and the weavers were not human!!

The scrolls delivered by Sankardeava at Barpeta were separated and what is on display are four major design sequences amongst the twelve separate strips of woven silk that were stitched together. There are four different design sequences amongst the twelve separate strips of woven silk that are now stitched together. 1) the Krishna scenes – from the 10th century text of Bhagavata Purana, 2) incarnations of Lord Vishnu and 3) text – in early Assamese alphabets and is a verse from the drama ‘Kali-damana’ by Srimanta Sankardeva tells the story of the defeat of the serpent-demon Kaliya by Krishna.

Garuda- Sankardeva had the verses also woven in the fabric

The scroll at the British Museum is not the whole piece. It was lost from Barpeta and was stored in the museum as ‘Tibetan Style silks!” It is made up of 12 strips, each one different from the other and sewn together in Tibet. Now how did this Vrindavani Vastra acquire a Tibetan makeover?

Migration from the palace to the Monastery- Lamas and Lampa

The famous textile lost its royal moorings and had a second history in Tibet. The weave travelled via the route of trade or loot you do not know. How and why did this huge and heavy textile travel so far can be an excellent theme for a whodunit.

The 12 strips were taken to Tibet. They were stitched together and then re-used as a hanging in a Tibetan monastery. It was now patched with a broad border made from Chinese-style silk material and on the top part of this textile, metal rings were attached to it to suspend the textile from the ceiling or the wall. It incarnated itself as a Buddhist Thangka.It was revered because it came from the land of Buddha!

How and when did it become a part of the British Museum collection? The journey to British Museum is the final chapter in this peripatetic tale of Vrindavani Vastra….Barpeta to Tibet to London!

Journey to London

The Vrindivani Vastra was acquired by Perceval Landon, a Times newspaper reporter covering the British military expedition to Tibet in 1903-4. Landan presented the textile to the British Museum in 1905.

The exile of the Royal Textile

The celestial tapestry was lost to the world, for the next 85 years! It was stored, filed and cataloged under the category as ‘Tibetan Silk Lampas’ – as Tibet was their last known place of origin! Finally by a quirk of fate and persistent efforts of Rosemary Crill, Curator of the Indian Department of London’s Victoria & Albert (V & A) Museum, the Tibetan identify the ‘Tibetan Silk Lampas’ as Vrindavani Vastra from Assam in 1992.

The exhibition opened in May 2016 titled- Krishna in the Garden of Vrindavan.

Standing in front of this piece you ponder over its journey. Feeble attempts have been made by the Indian government to get the Vastra back but you know that it is not coming back. You give a long lingering final look at the exuberant divine saga and step out in the London rain! You know for sure that it is going to enthrall you, haunt you and it will appear before that inward of your eyes as Wordsworth had so knowingly said! You will see the demon Bakasura being slayed by Krishna, you will hear the tapping of the Sattriya dancers, the humming of Borgeet will surround you and there will be no escaping from Sankardeva and his divine Vrindavani Vastra. After all it is Krishna and who can run away from him, more pertinently does anyone want to?

(This story first appeared in Virasat-e-Hind. The author is an avid travel and culture writer who loves to trace the history of Indian weaves and temples)